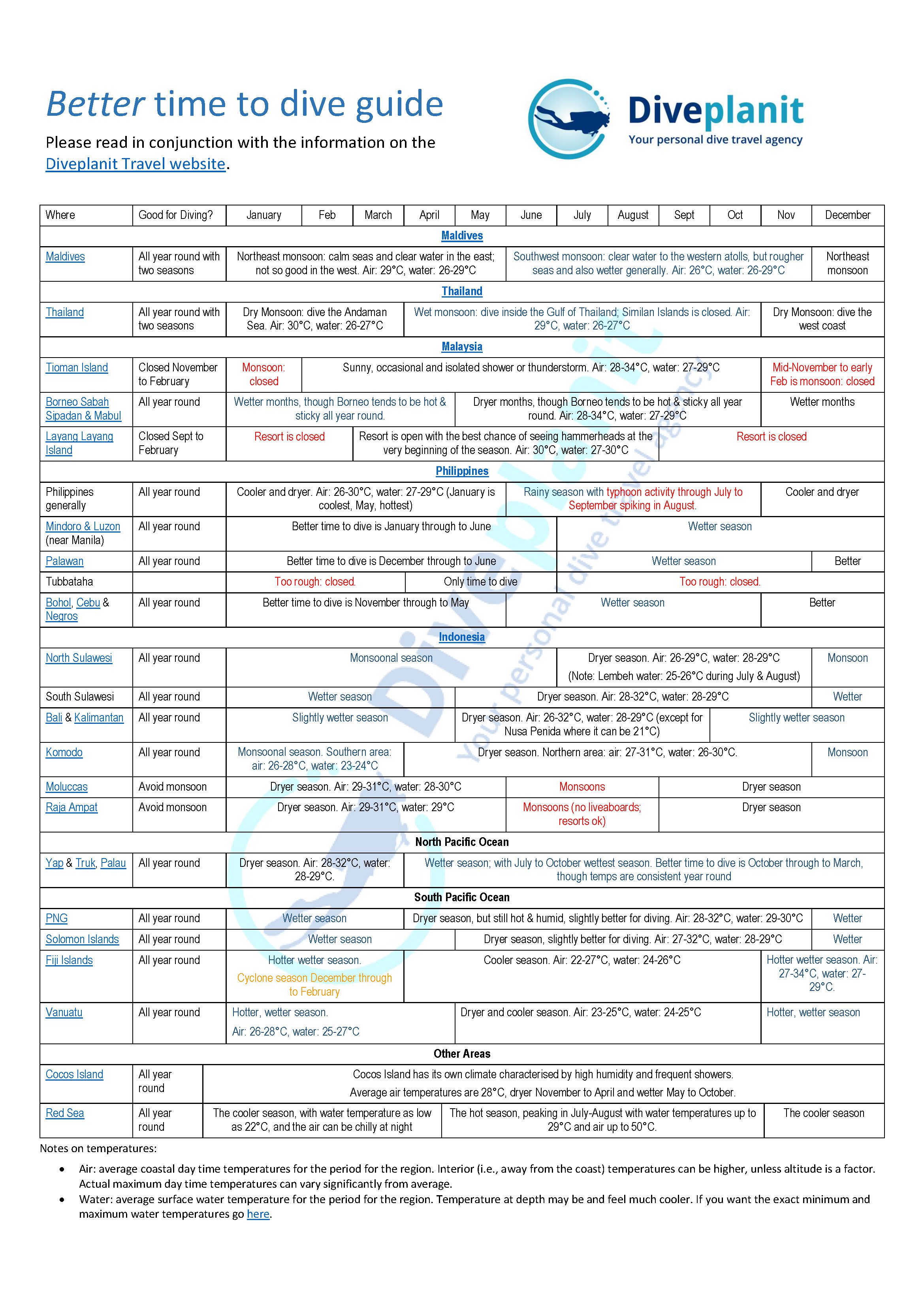

We’re often asked: “When is the best time to dive … {insert destination}?” So we put together this handy guide. Download a PDF version here … but please, please, please read the accompanying notes below.

Download a PDF copy here: The Best Time to Dive Guide by Diveplanit Travel – and to understand the very best time to dive in each destination, please, READ ON…

The best time to dive any destination depends on the local weather, and though it typically follows an annual cycle, it sometimes doesn’t. Overlaid on the annual cycle is the 14 year El Nina / El Niño cycle, and over the top of that is man-made climate change. So just because a destination’s wet season is reputedly December to March, don’t expect it to rain until 31st March, and then be dry as a bone from 1st April. Though we often talk about ‘the best time to dive a destination’, a more appropriate term might be: ‘the better time to dive a destination’.

Take away #1: there are no guarantees. If you can’t cope with a bit of weather – trade in that dive gear for a pair of knitting needles.

Visibility

The biggest impact the weather is going to have, is on visibility. Sure, it’s less fun diving in the rain, but in the tropics who cares about the odd shower. The weather can impact the visibility in two significant ways.

Significant Way #1). Stuff in the water that lives there, and is stirred up due to normally occurring currents, or turbulent surface conditions caused by winds – of which there are quite a few – though they tend to be predictable, and occur annually, in seasons. Unfortunately, Climate Change is changing some of these patterns, in most cases making storms, whether that’s cyclones, typhoons or hurricanes (see footnote*), more severe, and often extending the storm ‘season’. For example, both Florida’s hurricane, and Fiji’s cyclone seasons are noticeably longer.

Take away #2: don’t go diving when it’s blowing a hoolie – apart from the chance of not getting out at all, the vis will be crap – and possibly for a few weeks thereafter too.

Significant Way #2). Stuff that arrives in the water, and I’m not referring to the plastic pollution that is plaguing the planet – though that can affect visibility as we have seen from a video from Bali in early 2018 where there was so much litter in the water, you could hardly see the mantas. I’m referring to the river run-off, which typically occurs once the rainy or even worse – monsoon (see footnote*) – season has set in. Though this is a natural phenomenon, destruction of coastal wetlands and mangroves has led to a lot more sediment from rivers reaching coastal reefs, and affecting water quality generally. (This is the case even for Australia’s Great Barrier Reef).

Take away #3: don’t go diving towards the middle or end of any focussed wet or monsoonal period if you’re diving near any mountainous coastline.

It pretty much stands to reason then that you’ll get the best vis outside of the wet and windy months wherever you are. One reason why the Red Sea has such great vis all year round – it’s surround by desert with hardly a single river draining into it.

Ying & Yang

Many dive destinations, including big ones, like the Maldives, Thailand and Sri Lanka and even little ones like Komodo National Park in Flores Indonesia, have distinct seasons when one half, or even one side of the region is severely weather affected, whilst the other half isn’t and then vice versa for the other half of the year. This is great if you’re running a liveaboard dive business as you just follow the good weather. Not so good for a resort – though typically they are built in sheltered bays. If a resort is seasonally closed, for a month or so every year, then that would be the ‘least best’ time to go. However, typically, there will be ‘shoulder’ seasons either side of these periods – when great deals are to be had.

Take away #4: if a resort or a liveaboard has a special on – it’s for a good reason. It usually means: “We can’t guarantee great diving” but also “we’ll be half empty”.

Seasons

In the temperate zones, seasons make sense. They are reasonably well-defined and linked to a historic lifestyle of sowing, reaping, gathering nuts, and snow-boarding. In the tropics and particularly close to the equator, the seasons make very little sense. Wetter and dryer, and cooler and hotter are better ways to describe the climate. Don’t make the assumption that wet and cool go together either – as often it’s ‘warm and wet’ as in Fiji. Also, just because it’s ‘the wet season’ does not mean it will rain all day every day (like an English June). Typically it will rain (quite heavily) for a, usually short and predictable, period each day. Finally, reference to the ‘winter’ or ‘summer’ months in the tropics is not particularly enlightening.

One thing that tends to be seasonable though are school holidays. These might not impact so much the on availability at certain dive resorts or liveaboards, but they can have a big impact on availability of seats on planes, and hence the price of those seats.

Take away #5: Check, before you be very specific with your personal dive travel agent about which week you want, that you are not, for example, booking your flights smack bang in the middle of schoolies week. Be flexible.

Dive Region by Region

Cocos Island (Costa Rica)

Cocos Island has all year round diving as it has its own climate characterised by high humidity and frequent showers. Average air temperatures are 28°C, dryer November to April and wetter May to October.

Red Sea (From Egypt)

Red Sea has all year round diving. The hot season, peaking in July-August has water temperatures up to 29°C and air up to 50°C. The cooler season has water temperature as low as 20°C, and the air can be chilly at night.

Maldives

Diving conditions in the Maldives are dictated by two monsoon seasons. The northeast monsoon runs from December to May, bringing calm seas and clear water (20m to 40m visibility) to the eastern atolls, but often stirred up conditions on the western atolls (8m to 15m visibility). This is generally the most popular time for diving. From June to November the southwest monsoon brings clear water to the western atolls, but also rougher seas across the island nation. Fewer liveaboard options are available at this time of the year. Water temperatures in the Maldives vary from 26°C to 29°C, so a 3mm wetsuit is sufficient.

Thailand

Thailand’s south has two seasons with only a small temperature difference between them: 28°C to mid-30°C’s. Water temperature is consistent around 26-27°C. The west coast, on the Andaman Sea – where the Similan Islands are, experiences dry season, November to May, whilst the east coast has dry season March to November. Because of the strength of the wet monsoon, the Marine National Park in which the Similan Islands, the Surin Islands, and Richelieu Rock reside, are closed outside off the dry season. But during this time, you can dive anywhere in the Gulf of Thailand.

Malaysia

Malaysia is a country of two halves: mainland Malaysia, and Sabah and Sarawak perched on top of Borneo. Off the mainland coast, Tioman Island has sunny days, with temperatures around 28-34°C, occasional and an isolated shower or thunderstorm from February through to October. Mid-November through February is monsoon season and definitely to be avoided.

Borneo with similar temperatures tends to be hot and sticky all year round, though May to October are the dryer months. Its east coast dive sites like Sipadan Island can be dived all year round.

Malaysia’s Layang Layang Island, one of the southern Spratly Islands is closed September through to February, but otherwise has great diving when open.

Philippines

The Philippines has its own distinct climate but with regional variations. In general the cooler months are November through to February, after which it starts to get really hot (up to 35°C). The rainy season starts in July (slightly earlier in June in the central parts) with typhoon activity through July to September spiking in August, before cooling down again towards November – when it all starts again.

Indonesia

Most of Indonesia has its dryer season from April through to November, with Raja Ampat and the Moluccas in the north east of the country bucking this trend and having their monsoons June through to August.

- North Sulawesi: There is no real dry season, but the wetter season is November to June, so the better time to dive is from April through to November.

- South Sulawesi: The monsoon season is November to April, so the better time to dive is May through to November.

- Kalimantan: The difference between the wetter and dryer seasons is not extreme in Kalimantan. There are showers in the northern spring and autumn, so the better time to dive is from April to December.

- Bali: The difference between the wetter and dryer seasons is not extreme in Bali, and diving is possible year round, with the better time being May to September. The Mola Mola season is July – August each year.

- Komodo & Lombok: Komodo is one of the driest regions of Indonesia, with its northern region experiencing a short monsoonal period January to February. Fortunately this coincides with clearest and warmest waters on the southern sites. The better diving is from April to November.

- Moluccas: The monsoon season is reversed from the rest of Indonesia and arrives between June and August, when the sea can be a bit rough. Either side of the monsoon, March to May and September to December have the better diving conditions.

- Raja Ampat: The monsoon season is reversed from the rest of Indonesia and arrives between June and September, when the sea can be a bit rough. Some exposed resorts may close July and August. March to May and September to December have the better diving conditions.

PNG

Weather differs from region to region in PNG due to the high mountain ranges in the centre of the country. Mostly it is hot with high humidity all year round, with the rainy season generally from December to March and the dry season is May to October. Air temperatures along the coast are fairly constant at 28-32°C, with water temperatures of 23-27°C. With the exception of Milne Bay, which can be unpredictable in February and March, PNG is an all year round dive destination.

Solomon Islands

Another year round diving destination, as the weather is fairly consistent across the Solomon Islands, with coastal temperatures around 27-32°C, and water temperature 23-27°C. May to November being the dryer season is considered slightly better for diving.

Fiji Islands

The Fiji Islands have a warmer 27-34°C rainy season November to March, with the cyclone season December through to the February. The cooler season is April to October with 22-27°C. The better diving season is consider to be May through to November with the best vis towards the end of the cooler season before the rains hit and river run-off affects visibility.

Micronesia including Palau

These destinations which include Yap, Truk (Chuuk) and Palau, are definitely year round diving destinations, with year round air temperature of 28-32°C and water temperature of 28-29°C. The driest season is January to March, and the wettest, July to October, the better diving season is considered to be October through to March.

Notes on temperatures:

- Air: average coastal day time temperatures for the period for the region. Interior (i.e., away from the coast) temperatures can be higher, unless altitude is a factor. Actual maximum day time temperatures can vary significantly from average.

- Water: average surface water temperature for the period for the region. Temperature at depth may be and feel much cooler.

If you want the exact minimum and maximum temperatures, here is the definitive guide to sea temperatures for your next dive holiday.

* Footnote: Tropical Cyclone versus Monsoon

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterised by a low-pressure centre, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain. Depending on its location and strength, a tropical cyclone is referred to by different names, including:

- Hurricane: in the Atlantic Ocean and north-eastern Pacific Ocean, (either side of the US)

- Typhoon: in the north-western Pacific Ocean, (north of Australia)

- Tropical Cyclone: in the south Pacific or Indian Ocean, (east and west of Australia).

‘Tropical’ refers to the geographical origin of these systems, which form almost exclusively over tropical seas. ‘Cyclone’ refers to their winds moving in a circle, with their winds blowing anticlockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere.

A monsoon, on the other hand, is used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with the asymmetric heating of land and sea. Or in plain English: land heats quickly and air above it expands causing low pressure; air over the neighbouring ocean doesn’t heat so quickly but does get laden with moisture from the ocean causing high pressure. It naturally wants to move into the lower pressure area above the land, does so, and rises and drops all its moisture over the land in the process. Monsoons vary in intensity: often not too much wind, but lots of rain.

OK. Now you read far, you can have your own PDF copy: The Best Time to Dive Guide by Diveplanit Travel